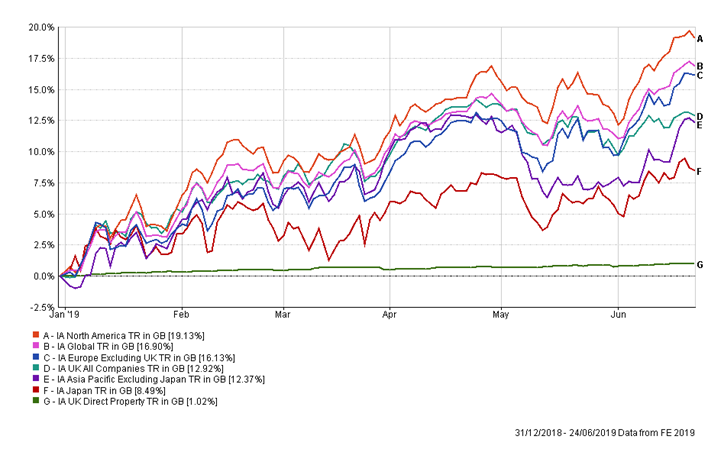

In July, the US economy will have recorded the longest period of expansion in history. Unemployment is at or near multi-decade lows in the US, Germany, Japan and the UK. And yet there are few obvious signs that the global economy is overheating. Sectors prone to exuberance are far from booming. Inflation – often the harbinger of economic doom – is notably absent. Indeed, it could be argued that a worry for the global economy is that inflation remains stubbornly low. Overall, despite its age, many commentators suggest that the global expansion doesn’t look to have reached its natural limits. The chart shows strong performance across all markets as we reach the mid-point of 2019.

However, political upheaval is threatening the outlook. The UK is looking for a prime minister as Theresa May has been forced to give up searching for a Brexit deal that can appeal both to her hugely divided Conservative colleagues and the rest of the UK parliament. The Italian government is at loggerheads with Brussels. And, of more systemic concern for the global economy, trade negotiations between the US and China appear to have broken down and Trump shows no sign of mellowing at this stage in his tenure.

At the root of the US-China dispute is a deep disagreement over technology. The US administration believes that the state-led subsidies China offers its tech sector provide its firms with an unfair advantage over US tech companies. Overlaying the issue of “fairness” is a concern that Chinese technology could also threaten US national security. Beijing denies the security threat and is reluctant to abandon the support it provides to its flourishing tech sector. There seems to be no common ground. Even if a deal can be struck in the coming months, it is likely to be partial and highly conditional.

The Fed is certainly under considerable political pressure. The US president has explicitly stated (via Twitter) that the Fed is a deciding factor in whether the US “wins” the trade war. We should be careful about assuming that because the Fed is operationally independent it is necessarily free of political interference. If the media “spin” is that the Fed is not a “national champion”, the public could start to question whether it deserves the powers afforded it. If the recovery falters, the Fed will be the fall guy. Donald Trump wants a second presidential term.

The damage from the trade war is likely to be seen most clearly in Europe. Europe is highly dependent on global trade and capital expenditure – the two components of global growth that are faltering. According to a recent article by JP Morgan, the European Union (EU) is also waiting to hear whether it is next on President Trump’s list of trade injustices to correct. The EU currently charges a tariff of 10% on cars that enter from the US, which compares to a tariff of 2.5% on EU cars entering the US. It is conceivable that the harder the US administration goes after China, the less it will risk adding the EU to the agenda. But that can’t be certain. Auto production accounts for as much as 5% of total GDP in Germany, so this is a sizeable dark cloud. It is interesting that such variations exist and outwardly evident that some equalisation would appear to be eminently equitable. No doubt there is a lengthy history that would reveal why such different tariff rates exist.

As we mentioned earlier, and who could have failed to notice, a new Prime Minister is being sought. The Brexit story is not a great reflection on UK politics. It is now 3 years since the referendum. In the immediate aftermath of the referendum the FTSE 100 and the FTSE 250 fell 9% and 12%, respectively. But since the close of the market on 23 June 2016, UK shares, as measured by the FTSE All-Share, have risen 28.1% as of 15 June 2019.The relatively stable global economic backdrop has been helpful. Global investors have bought into the so-called Goldilocks scenario; a “not too hot, not too cold” combination of stable growth, benign inflation and low interest rates.

Support for the UK market and the economy came from the Bank of England (BoE), which has kept monetary policy loose, ensuring businesses and markets have access to funding. However, the UK stock market has lagged global stocks. Since the Brexit vote, China shares have returned 42.1%, according to Thomson Reuters data; US stocks returned 41.6% and world stocks have returned 32.7%.

UK stocks have returned 28.1%, marginally outperforming emerging market and Japanese shares which returned 27.3% and 26.8% respectively. European stocks returned 17.5%. All of us investors share a common anxiety, which is normal human behaviour, but these returns are attractive and the challenge is to sustain this.

Douglas Kearney C.A. Investment Director

The above article is intended to be a topical commentary and should not be construed as financial advice. Past performance is not an indicator of future returns. Any news and/or views expressed within this document are intended as general information only and should not be viewed as a form of personal recommendation.