Overview

It has been another volatile start to the year, with equity markets reacting to an increasingly uncertain and constantly changing macroeconomic backdrop. We continue to see quite large daily movements particularly in US markets, but the UK and other markets are not immune. There are a myriad of opinions of what lies ahead, with little consensus. Most, if not all, will be wrong. Recession to be or not to be. Hard landings or soft landings.

The first four months of the year can be broadly split into three distinct stages: the false dawn which cheered us up through January; the reality, which happened towards the end of February; and then the banking tremors in March. Markets have been shaky since then, although some recovery seems to be underway as concerns about banking start to ease.

With each period, not only did market sentiment shift dramatically, but an absence of consistency was evident as both style and sector perspectives fluctuated. Over the period growth stocks performed well, as did European markets given a material improvement in energy prices and moderating inflation data. Emerging markets lagged, whilst value stocks performed poorly on a relative basis, and value-tilted sectors such as Financials and Energy underperformed. Fixed income, now operating in a higher interest environment, undoubtedly provides greater opportunities after a dreadful 2022, although not without some wobbles. Emerging markets and China are getting much positive commentary and generally expectations are high as the strength of the dollar recedes.

Banking Update

Inflation may now be peaking and may have already peaked in several economies as energy prices fall from the heights of last year, but interest rates may still have further rises to come. The Bank of England, the Federal Reserve and other central banks are signalling more rises should be expected.

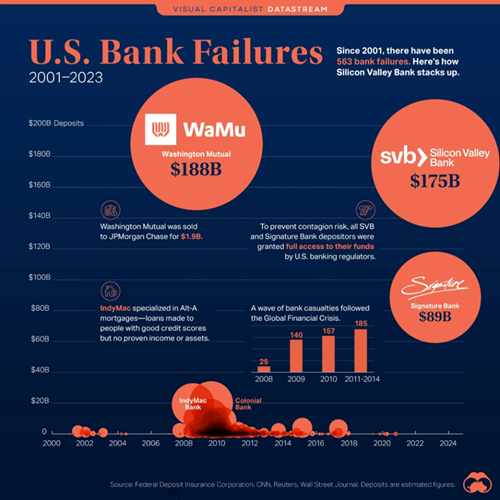

Whilst interest rate rises are good for savers, higher rates impact on the value of bonds. This is not news and has been known for centuries. Therefore, it was with some dismay that it we heard that Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) had found itself in distress.

Fears around the liquidity of SVB started in March and began to grow. It is probably the first-time social media has hastened an institution’s demise, and that has not gone unnoticed by the Central Banks. The run on the bank also accelerated at huge speed as money was withdrawn by a few clicks on a computer or phone. Again, a new phenomenon that had not been seen before.

What began as a regional bank run snowballed into a domestic and then quasi-international banking crisis with several associated consequences for institutions and markets alike. The SVB issue arose due to a fundamental duration mismatch: SVB had taken in a record amount of cash deposits from firms buoyed by favourable venture capital funding over the previous two years on the back of depressed interest rates, and therefore invested these into long-duration bonds.

When rates increased, the long-duration investments fell in value and these losses were ultimately crystalised when clients began to move deposits away from low-yielding deposit accounts into short-term money market funds offering better rates.

It is hard to understand how that was not foreseen and protected or why, after the crisis in 2008, all banks in the USA are not subject to tighter regulation as they are in the UK and Europe. We note that banking regulators are now looking at including all banks, which really is essential and much overdue.

As SVB continued to crystalise losses on its long-duration bond portfolio, investors began to question the true value of its asset book and whether it was indeed solvent. Panic then spread, mainly through social media, depositors rushed to withdraw their money causing a bank run, not only on SVB but also impacting a range of other regional banks.

This in turn caused distress for the international banks (notably Credit Suisse & DeutscheBank) and forced the Fed to step in and maintain trust in the banking sector by ensuring that all depositors would be made whole, containing the panic for the time being.

The perceived weakness of regional banks led to a rush of depositors moving money out of smaller banks towards the big four US names, which are deemed ‘too big to fail’ given their vast size and structural importance for the US economy. Alongside this, investors rushed to the relative safety of bonds, which caused prices to rise and yields to fall. The drop in US 2 Year Treasury yield was particularly sharp, contracting over 100bps in just five days.

It is thought that globally, banks have broadly tightened credit conditions and will likely make fewer loans amid the increased macroeconomic uncertainty. Even as the full impact of a tightening in credit conditions is yet to be known, history has shown that banking system weakness can have large and persistent effects on GDP growth.

Portfolio Cash

However, for us the banking system weakness shines a more fundamental light. Cash is an important asset in most portfolios and an important asset for liquid saving. The higher the cash exposure tends to be, the lower the appetite for investment risk. Cash must be a safe asset for investors and depositors: a haven where returns are sacrificed in exchange for security. Not in any way a risk asset.

What we have seen through recent weeks is a sense of the fear of a repeat of the banking crisis of almost 13 years ago. Reassurances were proffered, but certainty was not.

Rightly or wrongly, through concerns of contagion in the banking sector, the safety of the asset felt threatened and that cannot be right. Whilst some protection exists (up to £85,000 per banking group) it must be time that cash deposited or invested for meagre returns does not inadvertently become a risk asset. Cash must be fully protected, or at the very worst be protected to a much higher level. Holding cash in a portfolio should never cause anxiety of loss or fear of illiquidity.

It is encouraging that the Governor of the Bank of England has identified this need in the wake of SVB. Cash in portfolios or held for savings must be safe. Cash deposited is done so to avoid risk not to be under any threat. To place the responsibility on the individual to ensure exposure does not breach £85,000 can be complex and not as easy as it might seem. A plea going forward must be that cash is always a safe asset for individuals (and indeed cash within companies, many forming part of portfolios), ought not to be at risk.

Hopefully, with the banking crisis easing we can get back to the recovery phase. The ongoing US bear market has now lasted for more than 15 months. It is the longest bear market since the dotcom crash of 2000 and the sixth-longest since the Wall Street crash of 1929. Clearly, its relatively prolonged existence does not necessarily mean it will soon end. Although the S&P 500 has risen 14pc from its lowest point during the current bear market and is therefore closing in on the 20pc figure required to enter the next bull market, history shows that bear markets have lasted for as long as 21 months.

History, though, also highlights that bear markets have always been replaced by bull markets. And with bull markets having returned over 100pc on average, investors who buy a diverse range of shares during bear markets are very likely to experience vast capital returns over the long run.

Douglas Kearney C.A. Investment Director

The above article is intended to be a topical commentary and should not be construed as financial advice. Past performance is not an indicator of future returns. Any news and/or views expressed within this document are intended as general information only and should not be viewed as a form of personal recommendation.